History of Surveying

Some of the more remarkable architectural achievements of ancient civilized societies would have never been possible without knowledge of basic surveying principles. The Great Pyramids of Egypt and the Roman Aqueducts exist, in part, as a testament to the surveyor's skill. Less obvious, but equally significant are the various concepts, tools and methods established in the ancient and recent past that shape the modern land surveying craft. Our current system of land surveying and record keeping is actually a historically layered composite of techniques and concepts accumulated through time, originating as early as 5,000 years ago.

Ancient Innovations

One of the earliest known survey records comes from a clay tablet discovered in Iran. Dating back to Assyrian dynasty of Sargon of Akkad, this 5,000 year old tablet is a map delineating a surveyed portion of northern Mesopotamia. Other, slightly more recent, artifacts from this region represent survey maps of plotted agricultural lands and irrigation canals.

The Egyptians, who are credited with developing the mathematical system of geometry, surveyed and constructed the Great Pyramid of Giza with astonishing accuracy. The Giza pyramid (on average) measures one-sixteenth of an inch and 12 seconds in angle from being a perfect square. Unfortunately, no knowledge survives to this day of the methods and tools the Egyptians employed to achieve their incredible feats of engineering.

From the ancient Greeks, we find the development of geometric principles of triangulation and the invention of instrumentation to measure angles. 2100 years in the past, the Greek mathematician Eratosthenes calculated the circumstance of the earth to within 227 miles of its true distance by measuring the arc of a meridian. Eratosthenes' mistake lay in the assumption that the earth was a perfect sphere.

Return to top

The Roman Contribution

The Romans were the first to systematize land planning and surveying methods. The early Roman surveyors were called agrimensores (measurers of land). Roman surveyors were well trained. Their instruction provided them a knowledge of geometric principles, mapping, documentation, boundary definitions, as well as, surveying techniques as orientation, line sighting and leveling.

The groma was the primary tool of the agrimensores' art. The groma was a staff with four arms attached at the top. Each arm was set at a ninety degree angle with weighted string lines hanging from each arm. This tool allowed the surveyor to sight straight lines and determine right angles. Consequently, Roman land divisions were laid out in squares or rectangles.

Current "codified" methods and practices for land divisions within the United States can trace their present form to the techniques and systems developed by Romans. Upon the conquest of their neighbors, the Romans would inventory and record the wealth of their newly acquired colony. Part of this process required a comprehensive survey of the landscape. The Romans did not map these territories based upon data derived from natural geographical features. Rather they implemented a cadastre plan, a conceptual grid of pre-established units of land divisions based upon a coordinate system, and applied this plan to the actual or real land intended for sub-divisional delineation. The Romans surveyed the land according to the cadastre plan and marked the property boundaries. In addition, two maps were created. One map was earmarked for the Roman archives. The other a map, called a forma remained with colony. Property disputes within the colony were quickly and easily settled by referencing the forma. While the Roman system of land division and registry originated over 2000 years ago, its influence can be felt today within our current United States Public Land System.

Return to top

East vs. West

The United States Public Land System is also known as the "rectangular system." Prior to the Federal codification of the rectangular system, land surveys were performed utilizing a "metes and bounds" system of measurement that often relied upon natural features such as creeks, valleys and ridges to delineate boundary lines. This type of survey lacked the systematic approach of the rectangular grid system and, from a bird's eye view, the result was a kaleidoscopic pattern of land divisions. Most of the original Thirteen Colonies were surveyed in this manner, as well as, large areas in the southeastern United States, Texas and a few small isolated tracts in California.

The method of land surveying relying solely on metes and bounds descriptions on an ever-changing landscape is fraught with a variety of problems. After the American Revolution, the territorial limits of the United States began to rapidly expand westward. In order to satisfy the public debt incurred during and after the War for Independence, the government created a commission in 1784, headed by Thomas Jefferson, to sell off the newly acquired public lands. The task of this commission was to implement a process to measure and map land according to a standardized system. The final product produced by this commission was the Ordinance of 1785. This ordinance created the conceptual template for sub-dividing land, i.e., the rectangular system which underpins the procedural guidelines for surveying, describing and recording real property to this very day. Throughout the later years of the 18th century and early years of the 19th century, the U.S. Congress legislated additional statutory requirements to define and prescribe (and in some cases refining) the system for delineating the western territories. It was now up to the land surveyors to complete the process.

Return to top

Early U.S. Surveyors

A surveying party heading into the western territories during the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries contained at least a dozen to as many as twenty men. Included were a cook, teamsters, flagman, axemen, chainmen and of course a crew chief. Survey parties were provisioned for several months of work. Provisioning could include cattle to be butchered during the course of the job. Crews would also resort to hunting to sustain their larders.

Survey crews also endured all types of inclement weather, clouds of hungry mosquitoes and an often unforgiving and rugged terrain. In addition, confrontations with hostile Indians were occasionally reported. One early surveyor in the southwest admitted in his journal to setting a witness corner rather than confront the unfriendly natives occupying a bluff were the true corner fell.

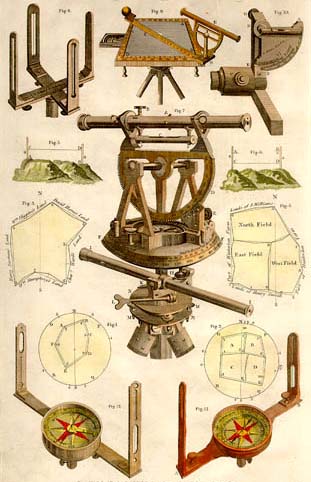

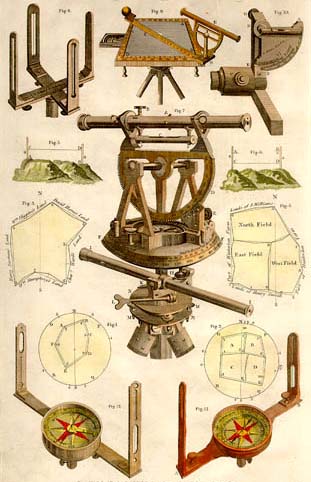

Despite the hardships, the early-day surveyors were able to accomplish the task of surveying all of what is now the western United States. The transit, compass, chain and ax were the primary tools of the craft; a far cry from the sophisticated technology available to the surveyor of today.

Return to top

Today's Surveyor

Modern technology has greatly enhanced the art of surveying. Instrumentation is accurate to one second in bearing. Distances are now primarily measured with lasers rather than chains. This is not to suggest today's surveyor is exempted from the harsh conditions weather and landscape. Modern surveying can still be very hard work even with today's innovations. To be certain, surveying in the 21st century is the result of a very long legacy of innovation and change accrued through the time-honored and tested contributions of the past. There are not many occupations that currently exist that can boast such a rich and dynamic tradition.

Return to top